First published in Medicus, February 2015 Volume 55 / Issue 1

Kiran Narula, President, Western Australian Medical Students’ Society

Kate Nuthall, President, Medical Students’ Association of Notre Dame

In The Poems of Exile, the exiled Roman poet Ovid wrote: “writing a poem that you can read to no-one is like dancing in the dark”.

While it may seem largely irrelevant to medicine, we suspect the frustration and disappointment expressed in this statement would be somewhat similar

to the challenges facing junior doctors who are unable to gain employment or training positions. The sudden flood of medical graduates has exposed a failure of postgraduate medical training to grow in line with the demand presented by this increase in graduates, leaving many junior doctors unable to fully realise their potential and ambitions due to a lack of training places.

It is an ironic position for our country to find ourselves in. For the past decade, we have been in the midst of a doctor shortage, affecting almost all specialties. Anecdotally, many Australians struggle to make same-day appointments with their GP. Given that we are now seeing RMOs struggling to find meaningful employment, surely we must ask ourselves, how this shortage first developed?

To put it simply, the planners got it wrong. In the early 1990s, the prevailing view was that there were too many doctors. At the time medical student numbers were reduced, entry for foreign trained doctors became more restrictive, and in 1996, the Federal Government cut the number of GP training positions.

While this may seem shocking, this was appropriate for the time – between 1996 and 2002, the number of doctors had increased by 12 per cent, double the rate of population growth.

However, what had not been forecasted was the change in work practices. Younger doctors began reducing working hours seeking a greater work-life balance. A Productivity Commission report (2005) estimated that a reduction of 30 minutes in average weekly working hours would translate into a reduction of around 530 full time equivalent doctors.

The realisation that these changes would result in a shortage of doctors came quickly thereafter, with the shortfall being predicted in a series of annual medical workforce reports produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). These reports stated that the number of medical graduates then would not be sufficient to meet population forecasts, and furthermore highlighted the extensive shortage of doctors in rural and remote Australia.

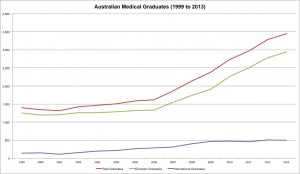

In response, the then federal health ministers, the Hon Michael Wooldridge and Hon Tony Abbott oversaw a large expansion in medical student numbers. Between 2001 and 2011 the number of medical students in Australia doubled to 16,491 through the opening of 10 new medical schools and expansion of places at existing schools. Our very own Notre Dame University medical school formed part of this national solution to workforce shortages, with the first graduates completing their studies in 2008.

The expansion of medical student numbers has been rapid and effective, so much so that the 2014 Health Workforce Australia (HWA) report on doctors recommended that “no change should be made to the total (domestic and international) medical student intake in 2015”.

This report begs the question – are we still in a shortage? It’s tricky to answer for it depends on location, specialty, and perhaps who you ask. As a guide, future modelling by HWA (2014) predicts both shortages and surpluses of doctors by 2021, depending mainly upon economic circumstances.

MALDISTRIBUTION & RURAL DOCTORS

There is an undoubtedly, however, a maldistribution of doctors. The HWA 2014 report stated that “per head of population, the gap (in the number of doctors) between inner metropolitan areas and the rest of Australia has widened further”. As such, every effort must be made to remove this inequity. However the idea that blindly increasing medical student numbers will somehow push doctors to work rurally is overly simplistic.

It continues to be shown that the three major ways of addressing the rural doctor shortage are providing rural experiences post-graduation, offering rural clinical experiences whilst at medical school, and recruiting medical students from rural backgrounds. Research recently released by the University of Queensland demonstrated that those who have studied at a rural clinical school were more than twice as likely to work rurally following graduation. This confirms similar findings previously released by UWA and other Australian universities.

Rural Clinical Schools (RCS) alone however are not sufficient to address the issue of maldistribution. Despite applications for RCS-WA outnumbering positions by nearly two to one in 2014, barriers to junior doctor positions post- graduation continue. Jobs for junior doctors within rural Australia are hard to come by. The withdrawal of federal support for Prevocational General Practice Placements Program is also set to limit the amount of rural General Practice exposure available for junior doctors. Until such time that we can increase capacity, existing problems are likely to continue.

MEDICAL STUDENT TRAINING

The recent surge in medical student numbers has pushed student-training capacity in WA to its limits.

In 2008, Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand (MDANZ) was commissioned by the Department of Health and Ageing to report on the national status of medical student clinical training in light of increased numbers. It found that existing capacity in all settings was concerning, with particular emphasis on Paediatrics, Emergency Medicine, General Practice, and Psychiatry. It also highlighted a number of barriers to expanding clinical placements including: the availability of suitably trained health professionals to supervise clinical placements, and a lack of appropriate infrastructure to support medical education in clinical settings.

Whilst the increase in student numbers has been largely beneficial for WA, in no way is this level of growth sustainable. We are especially concerned by plans to open a new medical school in the State. To date, there has been no follow-up report demonstrating the capacity of WA hospitals to accommodate the clinical training of additional medical students. From personal experiences, it is not uncommon to see six students on a surgical team ward round, nor to expect that there will be at least three students on a medical team. Before increasing student numbers, it is imperative to ensure that new students will be provided the same quality training whilst not compromising that of existing students. Anything less would be careless and irresponsible.

POSTGRADUATE TRAINING

The effect of increasing medical student numbers has led to a bottleneck in demand for Resident and Registrar positions. Previously, training places for specialties such as Psychiatry or General Practice would be left unfilled. This is no longer the case.

In 2014, WAGPET (the federal government-funded company for GP training in WA), in its annual report, stated there was almost double the number of applicants for positions. Additionally, since 2002 there has been a 400 per cent increase in GP training placements.

For residents (RMOs), the scenario is highly precarious. Following internships, the competition for positions is increasingly difficult, and the prospect of being unemployed after seven-plus expensive years of study is not only a daunting prospect but also a frustrating one. Educating doctors is not a cheap exercise, and to see such skills go to waste for a want of further training indicates a system that has failed to effectively plan and prioritise the future of the workforce. Finally, consider internships. Although positions were found for all graduates including Australian-trained international students in 2014, there continues to be an annual ongoing struggle to place all of these students. This year, we are extremely concerned – the combined total of medical graduates in WA will grow to just over 350, compared with 320 last year. Whilst places have always been found, these often arrive at the eleventh hour despite extensive notice. Such reactionary behaviour is again indicative of a lack of planning and foresight on behalf of policy makers.

A THIRD MEDICAL SCHOOL

Increasing medical student numbers or opening a new medical school in Australia at this time does not make sense. Given the present pressures, we are not convinced about the capacity of WA’s three major teaching hospitals to train future medical students and junior doctors. Therefore, after considerable thought, the Australian Medical Students' Association, the Western Australian Medical Students' Society, and the Medical Students' Association of Notre Dame have chosen to oppose the proposal to open a new medical school in Perth. This is not about maintaining a “closed shop”; this is instead about ensuring the training pathways of current and future medical students, as well as addressing the current shortcomings of the post- graduate medical education system. It is not good human resources management to have graduate medical students cooling their heels waiting for post-graduate training, nor is it fiscally responsible. Most importantly, under-trained doctors impact upon patient care.

The proposal by Curtin University to open a medical school in order to address WA’s rural doctor shortage, does not do any justice to rural WA. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends (2010) that in order to increase access to doctors in rural areas, medical schools should be located in such areas – Curtin’s plan would place their school in metropolitan Perth.

Per Curtin’s own proposal documents, it aims to accept only 20 percent of new students from a rural background. This figure is well below the Medical Training Review Panel’s (Federal Dept. of Health) goal of 25 per cent, and the WA average of 25.2 per cent (MTRP 17th Report 2014).

In addition, the proposal includes no plan to open any rural clinical schools despite established Australian research demonstrating the effectiveness of this program in encouraging doctors to work rurally, and global recommendations from the WHO to do so.

THE FUTURE

The future of Australia’s medical workforce requires thorough planning and carefully considered actions. It is too important to reduce it to the level of political point scoring or have it thrown around carelessly when a bump in the opinion polls call for it. What we need is a nationally coordinated plan – from the intake and training of medical students to the intake and training of general and specialist doctors – a role that Health Workforce Australia undertook until its abolishment. Until this plan can be clearly established, any changes to medical student numbers in WA could only be considered reckless and foolhardy. ■